Decoding the apple paradox: a critical discourse analysis of gender, technology, and nationalism in China’s digital space

Categorization of female images

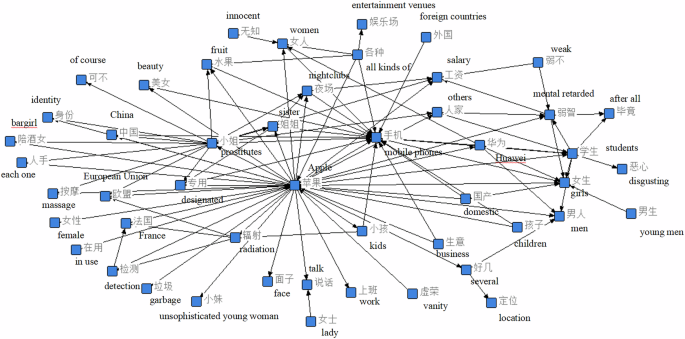

On the basis of the collected data, we utilized Rostcm6 software (a text mining software) to calculate the co-occurrence matrix and inputted the resulting matrix into Netdraw (network drawing software) to visualize the lexical network (referred to as Fig. 1). These analytical steps were undertaken to gain insights into the interconnectedness of keywords and to visually represent their relationships within the discourse surrounding the topic.

Lexical network of the key information in the Corpus.

The lexical network depicted in Fig. 1 centralizes around “Apple” and “mobile phone”, and signifies the sociocultural dynamics related to the usage of these technological entities amongst certain female cohorts. It contains an array of designators for women varying from neutral (e.g., “lady”, “sisters”, “girls”) to derogatory (e.g., “bargirl”, “prostitute”, “unsophisticated young woman”), the latter explicitly pejorative terms used on Chinese digital platforms to belittle women in the service entertainment industry. A deeper analysis of this network reveals disturbing contours of prevalent attitudes and stereotypes. Negative adjectives like “garbage”, “ignorance”, and “vanity” illustrate a deeply rooted bias and derogative tone. Notably, the incorporation of professional references like “massage”, “nightclubs”, and “entertainment venues” indicate systemic stereotyping and objectification.

Another intriguing glimpse into this lexical network shows how iPhone has come to symbolize a form of status currency for these marginalized women, fostering an illusion of vanity despite economic constraints. Interestingly, nestled within this narrative is a counter-narrative of nationalism, seen in the preference for domestic brands like Huawei and Xiaomi, with the latter often cited as an embodiment of patriotic choice due to its affordability and technological prowess, over foreign counterparts. In essence, this semantic network unveils a disconcerting nexus of gender bias, derogation, objectification, and nationalism.

To gain deeper insight into the portrayal of female iPhone users within the collected comments, we utilized the online corpus analysis tool Sketch Engine. As is a common practice in corpus analysis, Baidu stop words list was used to exclude items that carry little semantic meaning in the compiled corpus. By inputting “女 (female)” “ 妹/姐 (sister) ”, of any part of speech, as the query word, we then extracted a sub-corpus that focuses on female delineation with 3624 words in total. Therefore, we identified the keywords within the sub-corpus, thereby focusing on the portrayal of females. Significantly, our analysis prioritized multi-word terms, particularly bi-lexical phrases, over single word terms. This choice is substantiated by literature indicating that such compound expressions are prevalent in the articulation of feminist concepts on the Chinese internet. Notable examples include pejorative terms like “feminist bitch” and “feminist cancer”(Mao 2020; Wu and Dong 2019), alongside potentially empowering terms such as “female fist” (Yang et al. 2022) and “female boxers”. The latter, originating from the Mandarin term “女权” (nǚ quán, feminism), which has been pejoratively reinterpreted as “女拳” (nǚ quán, female fist), represents a disparaging reframe of feminism. This colloquial twist implies feminists as belligerents, metaphorically “throwing wild punches” in pursuit of excessive privileges. “Female boxers” further amplifies this metaphor, depicting feminists as aggressors within a combative arena, thereby accentuating the hostile portrayal of feminist advocacies as overly confrontational within the digital discourse.

After disregarding irrelevant characters, the ten foremost multi-word terms(with the value of relative frequency per million of the keyword in the reference corpus <0.05, which signifies the significant difference) were extracted, as shown in Table 1. Each keyword carries potential implications in the analysis and can serve as a pathway into understanding the perceptions and societal narratives constructed around these females.

Table 1 delineates three key subcategories within this inherited narrative, illustrative of the multifaceted gender biases inherent in this virtual sociocultural milieu.

Primarily, the term “小姐(Xiao jie)” appeared in terms of “KTV 小姐”, “小姐 机”, and “夜店 小姐 专业”, despite its historic origins as a respectful nomenclature for women, has, in certain contemporary contexts, metamorphosed into a derogatory term as the meaning of “a prostitute”, frequently tied to the entertainment or service sectors, indicating a stereotypical perception and stigmatization of this profession by society. This stereotype emanates further resonance within related terms such as “nightclubs” and “KTV bar”, inferring these women’s affinities to nightlife entertainment environments. The term “Simp”, a societal tag usually denoting men who excessively pander to unreciprocating women, occurs steadily. The inference here emphasizes these women as manipulative exploiters, entrenching the stereotype deeper within this sub-cultural narrative.

Next, the term of “factory girl” bestows an additional dimension to the stereotype, hinting towards an assumed economic bracket and professional identity about these women. The tacit suggestion lies in a presumed class hierarchy where these female iPhone users are often on a lower economic rung and perhaps engaged as low-skill operatives.

Quintessential to the analysis is “traitor”, a term that houses a multifarious narrative encompassing consumer behaviors, gendered narratives, and nationalist sentiment. Its application labels women choosing iPhones—effectively choosing a foreign brand—traitors, thereby creating a potent stereotype that pivots consumer choices towards a reflection of nationalist loyalties. This incorporation of patriotic duty into material consumer selection is an understated facet in gender studies, and it allows an intriguing dimension for examination. Remaining keywords such as “nightclub prostitutes standard” and “males from abroad” contribute to a gendered discourse, underscoring the stereotype within issues of gender politics, power dynamics, and societal expectation.

This study reveals a convergence between our preliminary corpus analysis of stereotyping female iPhone users on Chinese social media and wider scholarly discourse examining the media representations of sexual harassment and violence victims. Numerous studies validate that sympathetic media coverage of such issues largely relies on perceived sexuality, socioeconomic status, education levels, race, and ethnicity of the victims (Boyle 2005; Meyers 2013). Analogously, we discern a multi-layered stereotype of female iPhone users in China, illustrating them as economically constrained individuals, predominantly entrenched in the entertainment sphere, thus objectified. This infers a suspicion surrounding their morality, socioeconomic standing, and educational pedigree. Simultaneously, the ascription of treachery, purely based on their consumer preferences, resonates with the academic focus on racial affiliations.

In the following section, we will conduct a detailed analysis of this intriguing sociocultural phenomenon through an examination of the concordance of the previously mentioned key words, especially “小姐(prostitute)” “舔狗(Simp)” “厂妹(factory girl)” “汉奸(traitor)”, which remains as the main representative of the identities in the comments. By locating these words within specific texts, we aim to explore the prevalent stereotypes associated with female iPhone users as observed in digital discourse.

Defamatory tactics: labeling female iPhone users as sex workers

The intersection of gender and technology consumption forms a discursive terrain where sexist ideologies operate, subtly reinforcing patriarchal dominance. Discourse, in this context, serves as both a reflection and creator of societal norms. Stereotyping female iPhone users, as revealed by concordances, illuminates a gendered discourse that perpetuates patriarchal hierarchy.

In the digital realm of China, the intersection of sexism and nationalism crystallizes around the consumer behavior of iPhone usage among women, which is disparagingly codified through the term “小姐”. For instance, users denigrate female iPhone consumers with remarks like, “The prostitutes in KTV bars and nightclubs prefer using Apple products” and “Apple has now become a subject of ridicule! It is humorously referred to as the professional phone for nightclub prostitutes”. This kind of discourse does not merely indulge in an overt disdain for women but strategically employs sexism as a tool to uphold patriarchal dominion, echoing Kate Manne’s (2017) exposition on sexism functioning as a structural mechanism to police and preserve patriarchal systems by rigorously monitoring and modulating female comportment. The pejorative designation of female iPhone users as “prostitutes”—heavily laden with sexual connotations and emblematic of skewed gender power relations—exemplifies a misogynistic discourse embedded deep within the fabric of societal narratives.

This gendered narrative engages in a dynamic interplay with the principles of digital nationalism. The assertive discourse evidenced through social actor networks—the “prostitutes” as iPhone users and a “commenting community” characterized by apparent misogyny—mires in a digital manifestation of “observational control” where certain netizens assumes the authority to surveil, adjudicate, and deride the technological and consumer choices of women, essentially perpetuating a public-private dichotomy entrenched in patriarchal discourse. This not only delineates a gendered hierarchy favoring misogyny judgments but also subtly intertwines with nationalist fervor by positing domestic consumer choices as emblematic of national loyalty, thereby rendering the preference for foreign brands like Apple a deviation from the norm, subject to public castigation.

Furthermore, the discursive linkage of female iPhone users with “prostitutes” orchestrates their alienation from heteronormatively defined female identities, echoing Christina (2012) insights into the ostracization faced by feminists diverging from the patriarchal normativity in postfeminist contexts. This process of “othering” not only margins these women within digital spaces but aligns with the broader mechanism of gendered nationalism that seeks to delineate and enforce boundaries of national identity through the policing of gender roles and consumer behaviors. The esthetic denigration of this group, as conceptualized by Hill and Allen (2021), mirrors the utilization of anti-feminist humor to amplify perceptions of irrationality, further exacerbating their perceived deviation from normative femininity and, by extension, national loyalty.

The disconcerting phenomenon of digital misogyny within China’s virtual landscape profoundly illustrates the confluence of gendered nationalism and patriarchal ideologies, propelling female iPhone users into a contentious arena of technological modernity versus traditional Confucian values. This narrative transmogrification renders women not as beneficiaries of technological advancement but as hyper-sexualized entities, divergent from prescribed societal norms, thereby perpetuating an online reinforcement of misogynistic paradigms. Such derogatory characterization extends and exacerbates the antiquated dichotomy of the mother/whore, which positions the “good” women – those seen as maternal, self-sacrificial, and conforming (Tian and Ge 2024; Ge and Tian 2024), against the “bad” women, relegated to promiscuity and consequent disregard (Nagle 2017). This polarized gender narrative not only leads to a moralizing reading of sex, but also necessitates the vilification of sex workers who are assumed to infringe upon the boundaries of traditional female etiquette.

The strategic diversion from the iPhone’s technological merits to its gendered implications epitomizes populism, wherein a facade of concern for moral and national integrity masks a deeper current of toxic masculinity and potent misogyny (Kantola and Lombardo 2019). This discourse is typified by quotes such as “in the past, Apple was a symbol of wealth, but now it is exclusively used by prostitutes” and “the users of Apple devices can generally be categorized into two groups: prostitutes and traitors”. This pattern is indicative of populist strategies that leverage gender discourse as a means to galvanize and manipulate public sentiment (Kantola and Lombardo 2019; Bracewell 2021), intertwining with class struggles and fears around national security to rally against perceived external and elite threats (D’Attorre 2019). Within this framework, the polarization between “common people” and “corrupt elites”—often depicted through the lens of technology adoption—emphasizes an anti-elite narrative fiercely embedded in populist strategies (Hameleers et al. 2017; Hawkins et al. 2018). This redirection from appreciation of innovation to gendered critique mirrors broader societal tensions, where women’s engagement with technology becomes a locus for asserting patriarchal control and upholding nationalistic purities against perceived Western decadence. This discourse remarkably politicizes technological preferences, where gadgets such as the iPhone transcend their utilitarian roles, becoming symbols in the larger ideological conflicts surrounding cultural authenticity, governance, and globalization resistance.

Factory girls vs. simps: encrypted class conflict and threatened masculinity

Within the arena of discursive analysis, the contours of gender portrayal often find their origins in pre-established patriarchal principles. Transgression from these norms is often construed as disconcerting within societal perspectives and structures. A notable manifestation this discourse presents itself through the distorted representation of women iPhone users as “厂妹(factory girls)”, a descriptor linked to working-class milieu. This metonymous depiction is discordant with the actualities of the Chinese smartphone market, wherein iPhones noted for their higher price points, substantially surpass the pricing metrics of brands like Huawei.

The “factory girls” discourse further imbue the purported correlation between subsets of socio-economic classes and their predilection towards specific technology brands. Interestingly, these extracts disclose an incremental expansion in the classes represented, which is evident in statements like: “After observing for these days, it is indeed a fact that businesspeople, teachers, and civil servants typically use Huawei. On the other hand, KTV prostitutes, bartenders, and factory girls tend to use Apple. It’s really true.” Here, we discern the introduction of additional social actors: businesspeople, teachers, civil servants, who are synonymous with Huawei, while “KTV prostitutes”, bartenders, and “factory girls” are associated with the use of iPhones. Manifestly, such discourse appears to construct two widely disparate social strata based on technology brand consumption habits. Albeit the class construction starkly deviates from conventional wisdom, it intriguingly emphasizes the prevalent perceptions of social classes linked to their tech-usage behaviors. Notably, the extracts are replete with a plethora of words amplifying emotive undertones and modal affirmation, such as “indeed”, “true”, “certain”, and “undeniable”. This language usage suggests a heightened certainty of the actors’ social positioning based on their implied cell-phone brand preference, clearly demarcating them through social stratifications.

Wu and Dong’s (2019) scholarship provides a significant interpretive lens to unravel the latent motives driving the evident class divisions within the discourse unparsed from the comments section. They present an insightful conceptualization of misogyny as arising from unease surrounding economic disparities. This conflict, they argue, extends beyond the superficial realm of gender strife, unfolding instead as a veiled struggle of class dynamics meriting comprehensive scrutiny. Drawing from the analytical scaffolding outlined by Wu and Dong (2019), it transpires that such discussion subtly aims to undermine the socio-economic stature of female iPhone users. The discourse, interwoven with intricate associations of smartphone brand affinity with facets of social stratification and economic acumen, endeavors to mask organic apprehensions incited by these women’s consumer prowess.

The discourse surrounding women’s consumption of iPhones in China, and the consequent backlash from internet users, finds its roots deeply embedded in the dynamics of digital misogyny and gendered nationalism, revealing a complex interplay of societal transformation, anxiety, and power reconstitution. Manne (2017) captured this discriminatory treatment faced by women within the philosophical construct of misogyny. This concept targets and marginalizes “unbecoming women”, particularly those posing threats to hierarchical power structure by challenging the autarky traditionally held by men.

As iPhone-owning women, through their consumption behaviors, subtly challenge the societal and economic supremacy of Chinese males, these women engender an economic structural evolution. Despite the scarcity of comprehensive surveys addressing gender and income among Chinese smartphone consumers, available economic data shed light on a consumption-based misogyny, possibly rooted in a long-standing gender preference differentiation within China’s mobile phone industry. A 2018 survey indicated that women accounted for a slightly higher market share (50.1%) in the smartphone sector compared to men, with the iPhone’s market share standing at 26.5%. Notably, female users of iPhones (15%) significantly outnumbered their male counterparts (11.5%). Conversely, for domestic brands like Huawei and Xiaomi, which together held a market share of 27.6%, male users approximately doubled the female user base (MobTech 2024). Fast forward to 2024, brands such as Huawei have surpassed Apple in market share within China (IDC 2024). Further investigation reveals that among Chinese youth born between 1995–1999, Huawei emerged as the most preferred brand among males (33.7%), with a considerable proportion of these male “Huawei Youth” earning less than 5,000 RMB per month (MobTech 2021). By current exchange rates as of 2024, where 1 RMB equals 0.14 USD, this income level translates to approximately 700 USD monthly. This financial demarcation, particularly among male consumers favoring domestic brands such as Huawei and Xiaomi, points to a broader socio-economic narrative. It suggests a divergent consumer base where the allure of premium brands like iPhone among female users not only reflects their purchasing power but subtly contests traditional gender roles and socio-economic hierarchies by favoring globally recognized, higher-priced smartphones. In this transformation process from socioeconomic reliance on males to independent, sophisticated consumerism, women’s actions provoke anxieties amongst men, threatening patriarchal narratives of male predominance (Banet-Weiser 2018).

Probing further into the economic frameworks, iPhone emerges as a symbol of affluence, unveiling gender-disparities inherent in economic resource distribution. This revelation destabilizes the conventional male role as primary providers. The increased economic independence of women and their active participation in luxury tech consumerism can potentially intimidate and emasculate male power. This discourse propounds a narrative of resource expropriation by women, notably iPhone users, from men. The strategized stigmatization and delegitimization of women iPhone users’ tech-consumption behaviors attempts to alleviate male anxieties borne from class discrepancies that have become increasingly pronounced two decades into the twenty-first century. This period, characterized by China’s remarkable economic ascent yet accompanied by the gradual ossification of social strata, also marks a pivotal era for the empowerment of women. It witnessed an unparalleled flourishing of women’s agitation, notable both for its widespread participation and heightened visibility (Wu and Dong 2019). This consequently reestablishes male hegemony within a shifting cultural paradigm.

In the discourse analyzed within this study, a notable deviation from the conventional critique of Western consumerism, epitomized by the iPhone, is observed. Rather than indicting the iPhone as a symbol of Western extravagance, the narrative intriguingly elevates domestic brands such as Huawei, while concurrently relegating the iPhone to a token of “inferior femininity”. This discursive maneuver effectively accomplishes a cognitive displacement and transcendence of the iPhone, positioning it as a product catered towards a denigrated female demographic. This recontextualization not only subverts the expected valorization of Western technology but also evokes a nuanced form of digital misogyny intertwined with gendered nationalism. It not only underscores the bolstering of domestic brands as emblematic of nationalistic superiority but also delineates a gendered hierarchy of technology usage that mirrors broader patriarchal controls and anxieties. The relegation of the iPhone to a symbol of marginalized femininity, thereby, not only challenges the cultural hegemony of Western consumerism but also leverages misogyny as a mechanism to perpetuate nationalistic narratives, positing domestic technological consumption as emblematic of both national and masculine superiority.

The prevalence of the term “舔狗(simp)”—a social epithet assigned to men who excessively indulge and accommodate women with little or no reciprocation from the latter—in the corpus offers further evidence of an undercurrent of male anxieties feeling threatened, as shown in comments like, “Simp, where is the brothel? Men should go there and show their support” and “Creating how many unemployed simps in China”. The female iPhone user, through the confluence of the “temptress” stereotype and her individual consumption behavior, is accused of ensnaring a certain male demographic. Implicitly, these “Simps” then materialize as a tangible embodiment of male trepidation—an image of masculinity stripped of its traditional characteristics and framed as deviant. This mirrors the demonization of women iPhone users, thereby creating a parallel between these manipulated male archetypes and the denigrated female consumers.

The discourse analyzed herein vividly illustrates a profound societal unrest, catalyzed by the erosion of entrenched gender norms and the growing influence of Western consumerism. This discourse is not merely a reflection of male disquietude amidst shifting gender dynamics; it embodies a pronounced expression of gendered nationalism. The financial acquiescence of men to the consumerist desires of women, notably for foreign brands such as the iPhone, is critiqued not solely as a deviation from traditional gender roles but as an affront to national fidelity. Consequently, this rhetorical strategy, which vilifies both the “舔狗(simp)” and female consumers of foreign technology, serves as a multifaceted attempt to navigate and counter the anxieties sparked by these socio-cultural transitions.

Nationalistic guise: legitimization of misogyny

Consistent with established research conclusions that hint at a conspiracy implicating all feminists being in illicit collusion with foreign enemies of the state (Peng 2020), Chinese female iPhone users are maligned with similar prejudiced assumptions. The narration expounded within some statements like, “Go to the United States to find a foreign man as a husband and live there, rather than staying in China” and “The situation with Chinese women is really concerning. Whether it’s smartphones or foreign men, they seem to lose all sense in the face of temptation and vanity”, introduces an additional layer to our analysis—the polar opposition seen in the East versus West dichotomy. These excerpts demonstrate the commenters subtly reinforcing a stereotypic caricature, specifically the archetype of the “Western man”. Implicit within these claims is the insinuation that Chinese women display an increased propensity towards “Western husbands”, thereby initiating a subtle cultural critique. When this cultural binary is examined in conjunction with the narrative paradigms established earlier around women iPhone users as “prostitutes”, it creates a portrayal of these women as unethical “traitors” to their native cultural identity, who are expected to capitulate to the lure of the West.

The complex weaving together of anti-feminist sentiment and online misogyny with strands of Chinese nationalist rhetoric present an intriguing tapestry of socio-political maneuvering. This is not merely a chronicle of gender discrimination on digital platforms; instead, it unfolds as an elaborate interplay entwining the personal prejudices against women, specifically iPhone users, with broader trajectories of nationalism and political posturing (Nagel 1998). Herein, nationalist discourses provide a stage upon which hegemonic masculinities are performed and reinforced. According to Nagel, nationalism is a sphere where gender power hierarchies are established and contested, and masculinity, especially in its most assertive and domineering forms, is celebrated. The vilification of iPhone-using Chinese women, in this narrative, becomes an acceptable, even commendable act of patriotic defense.

This intricate correlation serves to legitimize the barrage of verbal attacks aimed at female iPhone users. The anti-iPhone female user campaign, under this lens, is reconfigured as an act of nationalist defense and an emblem of loyalty to the state. The assault on the women, thus, is strategically disguised as a nationalist initiative. The fervor of such patriotism then permits, even encourages, the identification and marginalization of a “disloyal” or “deviant” minority—the female iPhone users, whose alleged immorality is thus deemed a threat to the established social order.

The observance of such discourses provocatively highlights the alleged affiliations of female iPhone users, branding them as adversaries of Chinese men and devotees of Western and, more specifically, American males. This elucidates the persisting objectification of Chinese women as proprietary entities of Chinese men; any perceived deviations from this norm render the women as “easy girls”. In an alarming parallel, female iPhone users, in an analogous manner to demonized feminists, are constructed as usurpers of that which “rightly belongs” to men (Peng 2020).

As Peng (2020) contends, anti-feminists re-engineer feminism into a “symbolic accomplice of Western, masculine invasions” (95), a position which fuels the ire of Chinese male nationals. Misogynist behaviors and attacks on women are tacitly legitimized under this discourse, portrayed as defiance towards imported commodities and new colonialism, thereby diverting the blame for social inequalities and systemic flaws onto women. Reality, however, reveals an underlying antipathy rooted in deep-seated prejudices that uphold a strict patriarchal obedience as sacrosanct. Women, under this patriarchal narrative, are perceived as societal resources. They are expected to adhere rigidly to established normative behaviors, with deviations met with stiff intolerance. The ensuing binary narrative of East versus West serves as a crucial smokescreen, legitimizing gender disparities and perpetuating misogynistic dialogues, thereby consolidating patriarchal hegemony under the charade of “nationalistic resistance”.

The echoes of gendered ideological tension noted between supporters of domestic mobile phones and female iPhone users on social media effectively mimic that teeming between anti-feminists and feminists. The female iPhone users, much like feminists, break normative constraints of property and power linked to male ownership and nationalism. This perceived defiance or rupture of the established orders leaves them, like feminists, antagonized. It’s a delicate weave of personal prejudice, gender discrimination, and national pride, underscoring the intricate interaction of gender, technology, nationalism, and misogyny in the digital era.

link